How to Apply the Three Lines of Defense

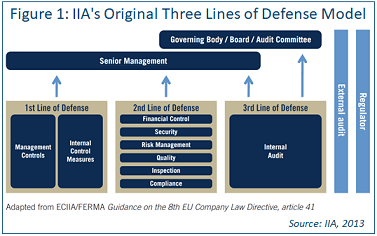

Since the three lines of defense model was first explored in a 2013 Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) position paper, many different interpretations of how the model could best be implemented have been released—some of which misunderstand the purpose of the second line. This piece explains why it is necessary to first understand how the lines work in the real world and then show how to use a framework to more practically allocate work among them.

Understanding the Three Lines of Defense

There are two problematic tendencies in business with respect to the three lines of defense. The first problem arises when people take the three lines of defense model and apply it to existing practices, effectively turning the model into a paperwork exercise but without driving any fundamental change.

The second problem occurs when people attempt to make changes and wind up creating an environment of distrust, where the first line views the second line as constantly trying to catch them in mistakes, while the second views the third line in the same way.

Before any work can be allocated across the lines, it is imperative to develop some consensus around what the three lines are expected to do. As originally conceived:

- First line of defense: Owns and manages risks/risk owners/managers

- Second line of defense: Oversees risks/risk control and compliance

- Third line of defense: Provides independent assurance/risk assurance

Unfortunately, this approach does not align well to how most organizations are structured.

In practice, the first line generally involves day-to-day business practices, although there is disagreement about how far this line stretches – with some focusing just on operations with inherent risk and others extending to all operations, including internal administrative work and all customer-facing work, such as sales and marketing. The third line is also well understood, focusing largely on what most organizations would term “internal audit.”

The second line is tricky, though, with a fuzzy mission around “overseeing risks.” The original paper openly recognizes the specific duties of this line will vary between organizations and that the second line is “independent-ish” from the first line, but not as independent as the third line. It is often unclear where the monitoring of day-to-day operations shifts from first line to second line. Similarly, it is unclear where oversight duties of the second line begin to blend with the oversight duties carried out by the third line.

Three Lines of Defense Complications

Three factors further complicate this simplified view of risk management:

- Risk ownership: The placement of risk ownership at the first line can cause complications, because this design co-mingles senior leaders who traditionally “own” the risk with the front-line workers who perform the day-to-day functions consisting of the overall risk management practice. It is common for real-world organizations to push the risk ownership up to the second line of defense, contrary to the model, simply because that is what the political realities of the organization dictate. This issue has been somewhat acknowledged in the 2017 clarification paper, although that largely focused on the tendency of organizations to place an ownership burden on the third line.

- Third parties: The original conception of the three lines of defense did not anticipate the now-common business practice of outsourcing significant aspects of the business to a third party. In an organization that outsources core operations—such as to a firm that provides both a cloud platform and services on that platform—much of the first line of defense is outsourced as well. But since it is impossible to outsource risk, the risk is still owned internally, although it cannot be controlled with internal resources. This circumstance effectively converts the first line of defense into a vendor management function.

- Co-mingling of duties: Ideal models have separation of duties between individuals. However, as we’ve seen with the rise of DevOps, separating duties by role rather than individual is also an accepted practice. With the three lines, the design is such that the second line of defense is responsible for creating risk models, identifying risk management frameworks and defining requirements—all duties often performed by risk owners, which should be placed in the first line of defense. This issue was also somewhat addressed in the 2017 clarification paper, focused on the need of the third line to retain as much independence as possible, and to be transparent about any conflicts of interest.

READ: How to Set Up a Strong GRC Program

Simplifying the Three Lines of Defense

As can be seen in the literature, the first and third lines are reasonably well-defined, with the second line largely taking on the work that doesn’t cleanly fit in the other two lines. Such tasks can be highly variant and dependent on business culture, structure, and politics.

To simplify the allocation of work across the lines, it can help to look at how the work is typically done across the lines:

- First line of defense

- Day-to-day business operations

- Implementing and using security controls

- Continuous monitoring of the controls

- Reporting to senior management

- Second line of defense

- Business tactical analysis/tactics, typically on a monthly cadence

- Identifying emerging issues and changes to external requirements

- Setting and adjusting risk management goals

- Consulting efforts with the first line to improve efficiency, coverage and risk management

- Reporting to senior management

- Third line of defense

- Independent analysis against standards, laws and regulations, typically annually

- Reporting to both senior management and board or audit committee

Looking at the actual duties of the second line, it is clear the original diagram from 2013 is flawed (see Figure 1).

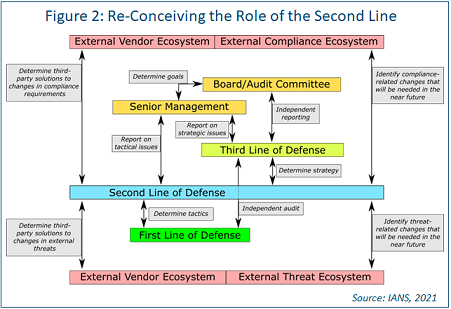

It works better to re-conceive the role of the second line as a translation and consultation service that streamlines work between the first and third lines of defense, as well as senior management and external factors (see Figure 2).

In this clarification, you can see how senior management and the board work to determine goals and communicate strategy to the third line of defense. The third line can audit against this strategy and communicate the results to the board. However, to remain independent, the third line cannot determine how the strategy is to be implemented tactically—nor is it in a position to provide guidance for how the organization should handle external factors. Similarly, the first line must be allowed focus to complete the day-to-day business requirements.

The second line is what makes the entire process function, taking in data about changes to the external compliance and threat ecosystems and how vendors can help address those changes. It works with the third line and senior management to determine strategy and consult with the first line on how that strategy is best implemented tactically, but it leaves the operational details to be determined by the first line.

With this conception, it becomes much easier to determine how work is to be allocated between the lines. For example, consider the NIST Cyber Security Framework (CSF) “protect” requirement, PR.IP-4. It states, “Backups of information are conducted, maintained and tested.” In the three lines of defense model, the first line would be responsible for implementing the technology to meet the required recovery time objective (RTO) and recovery point objective (RPO). The second line would work with senior management to define specific RTO/RPO requirements and lead the internal testing processes, while the third would be charged with verifying the backup process meets internal requirements.

Beyond the Three Lines of Defense

Reviewing the literature released since 2013, it is clear the three-line model has been challenging for a great many businesses, particularly around the fuzziness in the definition of the second line, which provides oversight, consultation, communication and (in some cases) monitoring services. However, by refocusing the second line on strictly consultation and translation services, it is easier to allocate work in an appropriate manner.

Although reasonable efforts will be made to ensure the completeness and accuracy of the information contained in our blog posts, no liability can be accepted by IANS or our Faculty members for the results of any actions taken by individuals or firms in connection with such information, opinions, or advice.